A Challenge for Even the Seasoned Practitioner…and No Match for the Unprepared

Nobody can be kinder than the narcissist while you react to life on his own terms.

-Elizabeth Bowen

Anyone working with those with a substance use disorder (SUD) understands the challenges associated with engaging individuals in a discussion regarding the merits of changing personal habits and behavior. Attempting such a conversation with someone whose personality suggests narcissistic tendencies if not a DSM-5 diagnosis (see https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/evolution-the-self/201311/6-signs-narcissism-you-may-not-know-about) can test the skill and patience of even the most accomplished practitioner.

Whether working in counseling with an individual dually diagnosed with a substance use disorder and a personality disorder like narcissism or living with someone who might share these co-occurring traits, they can try one’s patience, make us question ourselves and our competence, making it easy to feel like we are the crazy ones for getting so frustrated. The fact is that approximately 50-70% of substance use disordered individuals will have a mental health disorder at some time in their lives and supporting them and treating this aspect of their illness is essential to their recovery. The good news is that, although personality disorders can be quite resistant to counseling, there are built in supports and protective factors in most substance use recovery programs and therapies that offer hope and resources for those individuals willing to seek help. The curative protective factors tend to include structure, supervision, social support and engagement in activities free of alcohol and other drugs. Such activities offer competing ritualized healthy dependencies on more pro-social behaviors. Working or living with individuals with these co-occurring traits involves finding ways to support their efforts in these directions.

For the sake of discussion in this essay, assume you are counseling someone with a SUD whose actions routinely frustrate co-workers, demoralize subordinates, and alienate significant others. As your client rails about “the nerve” of his staff to question his judgment and proceeds to question the love or loyalty of acquaintances and family who dare challenge his authority, you begin to realize that this particular individual likely presents with more than the usual interpersonal conflicts associated with a SUD.

Alerted to the possibility that your client presents with what may represent mitigating personality issues, you broaden your questioning while conducting your history, seeking to better understand his interpersonal relationships. These questions are intended to discern your client’s perception of these interactions with others and, more to the point, how these “others” perceive your client…or at least what your client reports regarding “his perceptions of their perceptions.”

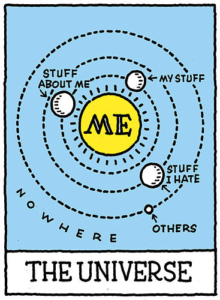

Considering your client’s responses to your questions, you realize that every relationship is described in very “black or white” terms: Her concerns are unjustified as she is not as well informed as I am; I know more than everyone in that department combined; his loyalty is in question so why should I concern myself with his opinion–he can’t be trusted; those who know me best know what I stand for and that I alone can be counted on to do what is needed. According to your client, there are two types of people with whom he must interact: those who support him unconditionally and dutifully back his position, and those who do not, and therefore cannot be trusted or who at best lack the requisite credentials to even question his will. At this point, you begin to suspect that the individual with whom you are working presents with mitigating disorders; a SUD and some form of narcissism if not a personality disorder (see http://bit.ly/1NPTlnU).

Narcissistic individuals are, as Charles Strangor notes in his textbook on social psychology, Principles of Social Psychology (see https://opentextbc.ca/socialpsychology/), not known as endearing individuals:

People do not normally like narcissists because they are unrealistic and think only of themselves…Narcissists may also be obnoxious, continually interrupting and bullying others, and they may respond very negatively to criticism. Although they make positive first impressions, people eventually see narcissists less positively than narcissists see themselves, in part because they are perceived as arrogant (pp 206-207).

Such individuals are at best challenging clients with whom to work in a clinical relationship where objectively reflecting on one’s personal behavior is a focus of primacy if any benefit is to arise from a practitioner’s efforts. Even when employing the most collaborative of strategies when interviewing, practitioners can quickly find themselves perceived as incompetent or worse yet, disloyal if proffering anything perceived as implying that the client’s view of reality warrants review let alone change.

Acting on these issues, should they arise in a relationship, rather than reacting to them necessitates both an understanding of narcissism as it manifests itself in individuals as well as establishing firm boundaries in the clinical relationship. Counseling such individuals is not for the faint of heart nor those whose self-esteem and sense of efficacy as a practitioner is in question; this is true of working with individuals presenting with any personality disorder. That said, for an excellent review of proactive steps to take when dealing with individuals displaying such characteristics, read Shari Stein’s excellent essay, The Arduous Work of Treating Narcissism: A Therapist’s Guide – http://bit.ly/2vjc6wC

As narcissism presents itself in relationships beyond the therapist’s practice, consider sharing this essay beyond the field of counseling if you deem it appropriate.

Robert J Chapman, PhD & Jeremy Frank, PhD CADC

Robert Chapman is a psychologist and retired faculty member from Drexel University where he served as Associate Clinical Professor of Behavioral Health Counseling and currently consults in issues of Alcohol and Other Drugs in higher education (https://www.linkedin.com/